The Bible is a BIG book.

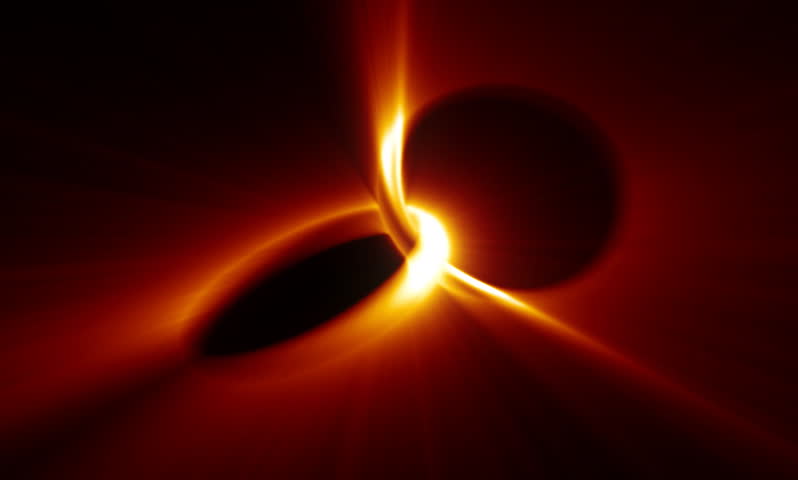

It is “big” not only because its contents take up many thin, silky pages, but because it spans many lifetimes. It is a “big” book not only because it contains many plotlines, authors, streams of thought, and depictions of history through particular Hebraic lenses, but because it contains a veritable heartbeat, albeit varying in palpability at times, of a people and their God. It is “big” not only because its beginning is too mythic and cosmic in scope to be easily pinned down by western modernity, but because its ending is no ending at all in the traditional sense, but rather, a cosmic invitation into the continuation of a myriad of plotlines already in progress.

The Bible, as I have come to learn, is a BIG book; too big for one dedicated lifetime to neatly box up, explain, decode or unwrap. Based on my dedicated biblical studies these past 20 years, I have concluded that the Bible is Big (capital “B”).

It is bigger than me.

The Bible as it sits in my hand is not an ordinary book. It does not have one author, but a team of oft-disconnected authors and editors. It was not written or completed in any one segment of time but has been worked, worded, and reworked over generations reflecting multiple mindsets, agendas, and time periods often in short spans of text. It does not seem to reflect any one dominant agenda, but depending on the lens with which the reader brings to this epic conglomeration, it has the capacity and power to say and speak into a vast ocean of situations and seasons. The Bible does not contain a dominant genre but instead blooms with various styles, hymns, ancient mantras, genealogies, myths and legends, poetry, rhyme and meter, apocalypses, law codes, rabbinic exaggeration, recounted visions, and detailed historical narrative, to name a few.

All of this contributes to the Bible’s vastness and complexity. It is this complexity which gives rise to many divergent approaches all bent on attempting to hear the arrhythmic heart beat within and behind the text. What do these stories mean? To whom are they intended? Can a generation thousands of years removed from the time period of a text’s writing fully unveil its intended meaning? In so doing, does the meaning of old have the capacity to overcome the language and context barriers now existent to be relevant to readers and communities today? The interpretive task is daunting and the trees that have sacrificed their days reaching toward the heavens, and the ever-refilling inkwells all speak to the inexhaustibility of chasing down and capturing once and for all “the” concrete message of the Bible.

Yet, it speaks.

And there is every indication that it will continue to speak, even to the very end of the age. How it speaks and what it is allowed to say is substantially dependent on the community who has chosen to squeeze its contents to extract the life-breath existent in the text. By this I mean the approach one takes in ascertaining what the Bible says and why it says it is inescapably determinative of the breadth, be it sweeping or narrow, with which any particular text can speak.

For example, approaching the Bible with the fact-finding tools afforded by the “higher critical” methods from the Modern Era grant many advantages for the reader. There is an assumed concreteness in historical facts and provable scientific theories that produce a seemingly stable platform from which to declare what a particular text is referring. Likewise, the perceived ability of the reader to “decode” lost hymnal material, early creedal statements, or discern poetic meter in the voice of the Prophets affords a certain level of factual critique. And that critique leads to “natural” conclusions about what a particular text was saying in the day it was worded.

However, weaknesses and veritable cracks have been spotted in the foundation of these historical/critical methods of Biblical interpretation. The main source for the cracks is the unmasking that any pseudo-historical study is as susceptible to subjectivity and creative manipulation as any other discipline that has been applied to Biblical studies.

How a person interprets history, perceived sources, unknown editors, etc. is a huge determining factor as to what that person is capable of reading both into and out of the Biblical text. What the history-as-fact methods of Biblical interpretation sought to do by “factualizing” the times, sayings, and settings of the Bible has, in fact, turned out no facts at all. The historical lens is simply that, a lens through which to see a certain quality in the vast spectrum of Biblical interpretation.

The Enlightenment of the 1700s with its subsequent Modern Era has produced many valuable contributions to Biblical study and interpretation. However, the Enlightenment’s project to develop the lens from which to interpret the Bible and subsequent ontological truth has failed. Each method is as subjective as its predecessor. Yet, each method illuminates a facet in the complex conglomerate of Biblical studies.

This unsettling realization concerning the past 300 years of inability to lock down once-and-for-all-concrete-dogma and ontological meaning has given rise in recent years to a more narrative approach to the whole of scripture. The narrative critic embraces the realities of post-modernity by rejecting the Enlightenment’s claim to ontological reality based on historical reason and its ability to unveil Biblical certainty.

The narrative critic is likewise not sold toward progressive liberalism (i.e. humanity is destined to get better and better until all evil and injustice are done away with through human means), but rather seeks practical theological meaning in and through the Biblical story. By embracing the claims of postmodernity, the narrative theologian concedes that “we cannot survey history from some universal, purely rational point of view…we have no choice but to operate out of the historical narrative in which we find ourselves—and for the Christian theologian that means the Christian narrative, shaped by the story(ies) of Jesus Christ as found in the Bible.”(# Garrett E. Paul, Why Troeltsch? Why Today? Theology for the 21st Century.)

The narrative critic is intimately concerned about this story’s implication from today and for today. It is in light of the Biblical story, informed as it can be from historical subjectivity, that the narrative/postmodern critic arrives at the questions concerning what can be gained today in the middle of our present Christian narrative concerning gender roles, ethnic cleansing, homosexuality, God at work in society, etc. The narrative theologian is readily able to access the multifaceted world of historical critical methods, but now from the vantage point of allowing the narrative to speak broadly into the vast ocean of present contexts instead of focusing narrowly on one rationally concluded ontological truth.

Admittedly, this approach is still being worked out. It appears that some are more comfortable than others at stretching the boundaries concerning what and where and how the narrative of the Biblical story can speak into the ongoing story/narrative of the present reader. Naturally then, the ground is fertile for the growth of ongoing approaches concerning the Bible and its interplay within present society.

Concerning the next wave of Biblical interpretation, I can say that I am not sure exactly where it is heading. However, as a budding young theologue having benefited from the rich and various stylistic tutelage of today’s methodological stew, I have developed a real affinity toward what I loosely understand to be “applied context”. Unapologetically stemming from the postmodern mindset and certainly a continuation of narrative approach, the applied context method of Biblical interpretation seeks to employ historical/critical methods to paint the picture from where a particular text derives, attempting to appreciate the divergent approaches that illuminate the natural tension existent in various approaches to the text. As well, it employs the narrative critique to understand its placement in the context of the Biblical narrative as a whole. It seeks to locate itself within the arrhythmic heartbeat of the Biblical corpus embracing both its adherence to and tension within the dominant story. Furthermore, it seeks to stretch beyond the boundaries contained within the bound story to find its way within today’s continuation of the Biblical/Christian narrative.

Where the story is heard has as much impact on its meaning as what the story was written down for in the first place.

The context of the person reading brings definition to the individual text as it is lodged in both the broader Biblical story as well as the ongoing present reality of the reader. Yet the ancient intent; that is, the context within which it was produced or refined, if discernable, is equally able to bring shape to today’s present context. In this way, context is embraced in it totality attempting to hear in two directions: from past context to the present world reality as well as from present reality back into ancient context.

Today’s narrative reality; that is, the narrative story of Christianity on display today in the lives of its adherents, is just as informative to the Biblical text as the original context from which the Biblical narrative, in part and in whole, was produced. The underlying assumption contained in this approach is the understanding that the Bible speaks…always present tense. From its conception in spoken word and written form to its reverberation throughout history, the Biblical narrative is invitational, inviting the hearer/reader into the story already in progress. Yet, it is inseparably historical in that the reverberating words and texts have been forming a relational story long before you or I heard the invitation into the drama.

The Bible is Big…capital “B” remember…Big because of its ongoing present tense. The words, spoken and written and rewritten, hymnal formulae, historical narratives, Prophetic proclamations, letters to fledgling communities, etc. seem to continually speak in the present tense since their initial proclamation. In so doing, the words of any biblical story always contain the power to shape the present reality of the reader and his/her community.

At the same time, the community and/or individual’s context can intensify or nullify certain qualities of what is received in the reverberating word. A present context simply may not be able to perceive certain nuances inherent in the reverberating story thus producing an understanding of the Biblical narrative by accentuating what it does perceive and inadvertently leaving other ancient contextual realities to be heard by successive hearers and generations and contexts.

And yet, it speaks.

It speaks from ancient communities into present community contexts. What it says, or rather is allowed to say, is defined by the present community context seeing and hearing the scriptural narrative through the spectrum of its own reality. Arguably, then, the Bible has the capacity to speak endlessly into an ever-changing world with a reverberating present-tense truth (eternal?) consistent in the overarching narrative of the Bible as reflected in any setting and context now and into the future.

The NOW Word

The task of the church is to discern the “now” word of the Biblical and Christian narrative consistent with the ancient contexts that first produced it as well as the present contexts in which that reverberating word is seeking to speak anew. Closely affiliated Biblical fundamentalists have often stood on the eternal nature of God’s word, narrowly defining that word to the leather-bound pages of the Old and New Testaments that we know as the Bible.

Yet, now the church stands at the door to understanding God’s word contextually more broad allowing the discernable truth from the ancients to inform the realities of today and visa-versa. The context of today is equally able to eternally speak back into the ancient contexts of the Bible as the search for God’s “now” word continues in the ongoing present on into the future.